Optimising session key storage in Redis

Tracking authenticated user sessions can be implemented in Redis using setex with some serialised JSON. It works pretty well until you have to cope with millions, or even tens of millions of sessions where the memory usage and performance can suffer.

By using Redis data structures more effectively we can achieve a 70% reduction in memory usage, at the cost of both code and conceptual complexity. Is it worth it?

Baseline implementation

First let’s create a Session class as our starting point which will use an expiring key to hold each session in Redis. The attributes we care about are:

-

id, a long random token identifying the session -

identity_id, the identity of the user who owns the session, and -

expires_at, the time at which the session expires

All this code is simplified and adapted from the real version, with the assumption that redis is an available Redis connection, but it should be sufficient for the purposes of this post.

class Session

attr_accessor :id, :identity_id, :expires_at

def initialize(attributes)

self.id = attributes[:id] || SecureRandom.hex(20)

self.identity_id = attributes[:identity_id]

self.expires_at = attributes[:expires_at] || 30.days.from_now

end

end

We’ll need to add a save method which uses setex to save the key with an expiry time, storing the session attributes as a JSON blob.

def save!

ttl = expires_at - Time.current

data = { identity_id: identity_id, expires_at: expires_at.to_i }.to_json

redis.setex(self.class.key(id), ttl.to_i, data)

end

def self.key(id)

"session:#{id}"

end

We also need the opposite method to find a session we’ve previously stored using the get method to fetch the key data.

def self.find(id)

data = redis.get(key(id)) or raise 'Not Found'

attributes = JSON.parse(data).merge(id: id).with_indifferent_access

attributes[:expires_at] = Time.at(attributes[:expires_at]).utc

new(attributes)

end

Hopefully there’s nothing too controversial there. The implementation is short and easy to understand, and the keys and values stored in Redis are human readable which can be useful for troubleshooting. It gives us a good starting point to see what effect various optimisations have on memory usage.

Benchmarking

To make sure there’s nothing else in Redis flush the databases and check that only the minimum amount of memory is being used.

$ redis-cli flushall

OK

$ redis-cli info | grep used_memory_human

used_memory_human:984.64K

Then in irb we can start populating sessions by repeatedly inserting 100k sessions:

irb> 100_000.times { |n| Session.new(identity_id: n).save! }

=> 100000

For every iteration we query the Redis memory used:

$ redis-cli info | grep used_memory_human

used_memory_human:24.95M

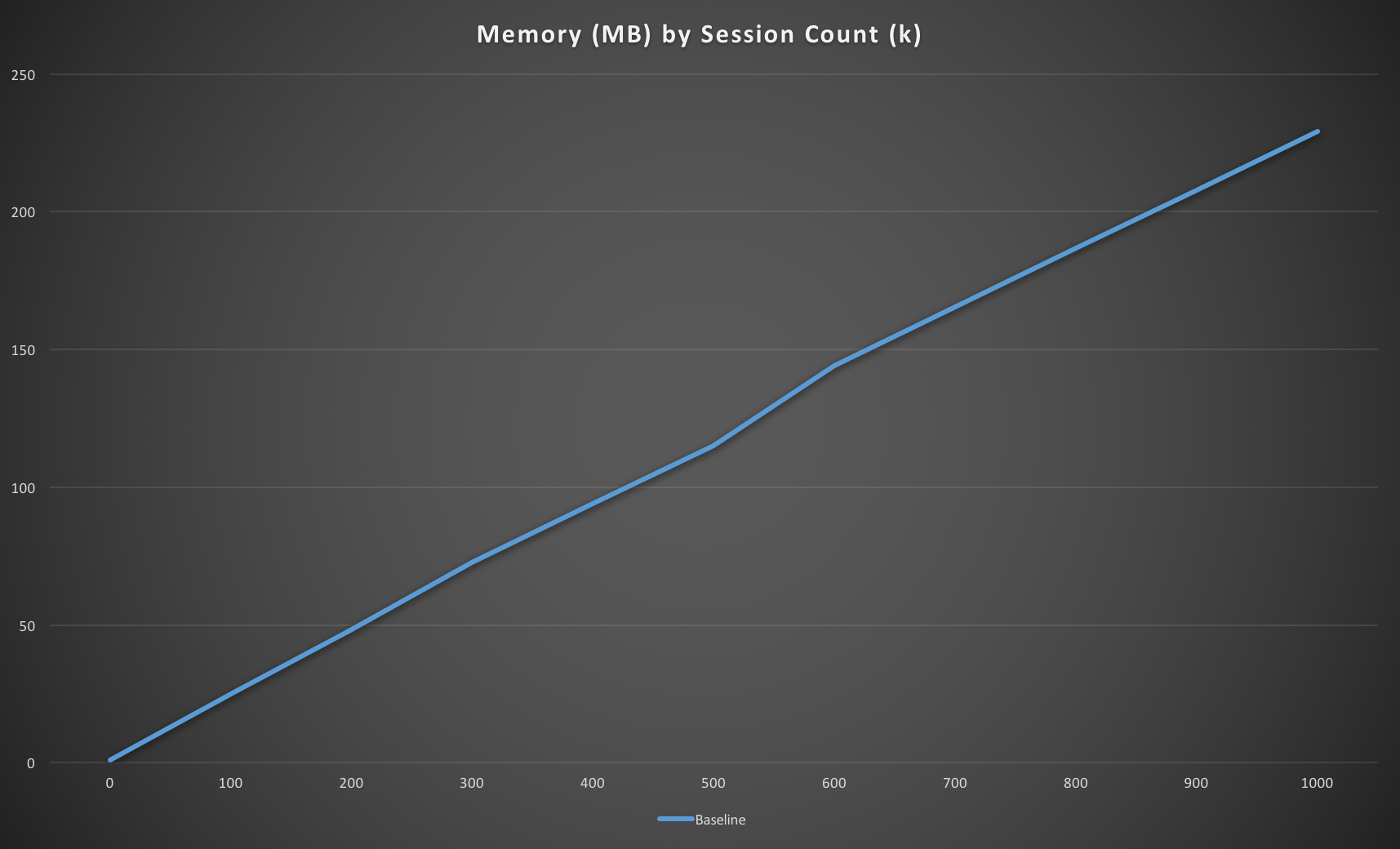

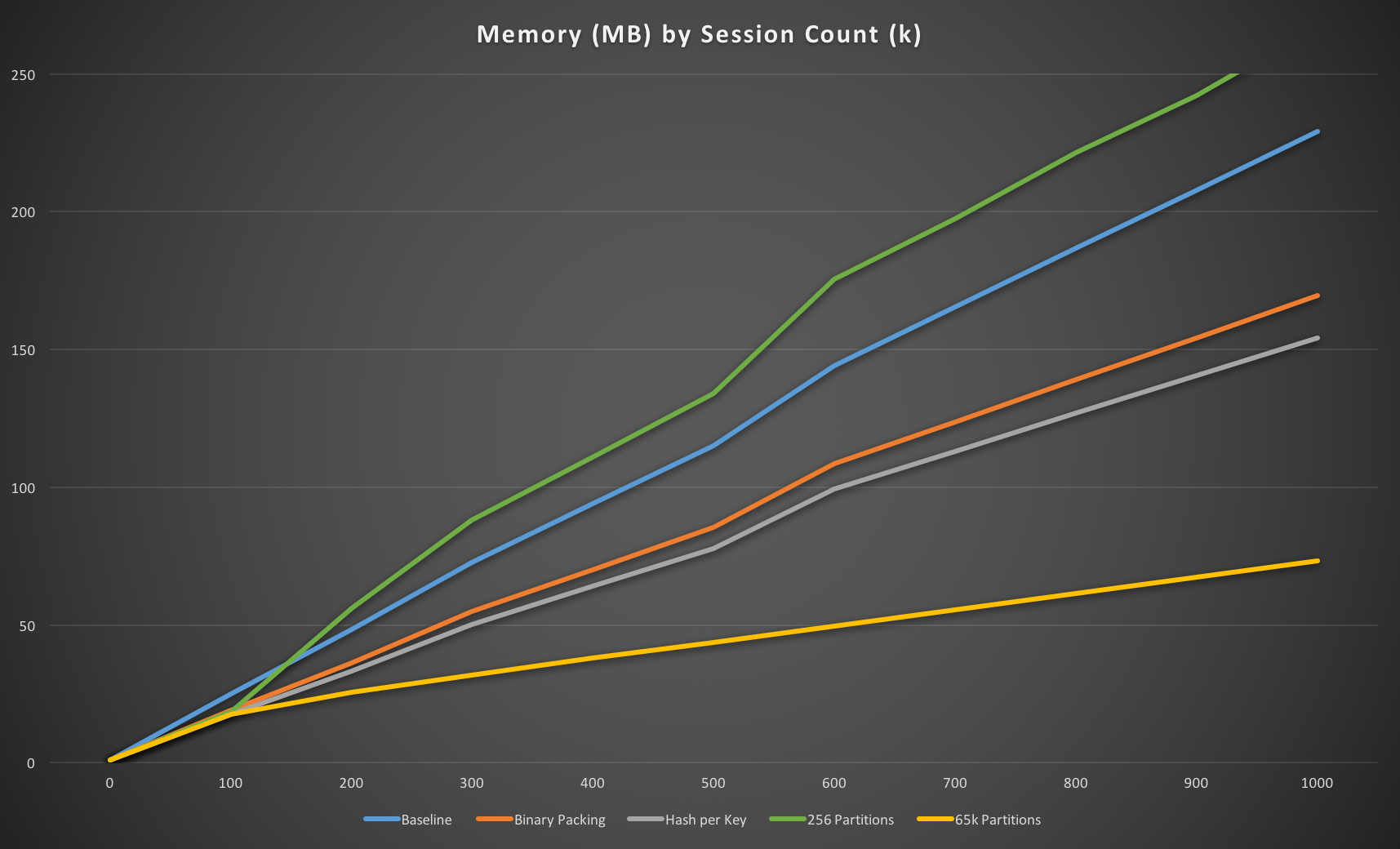

Repeating this process until we’ve got a million sessions stored gives us enough data points to be able to see a trend emerging. This gives us our baseline memory usage for the quickest and easiest implementation:

The memory usage is linear, as you’d expect, and we’re using around 230MB to store every 1M sessions. This seems like quite a lot as we know our key size is 48 bytes (“session:” plus a 40 character string) and the data averages out at 45 bytes, so we might reasonably expect memory usage to only be around 93MB. This indicates there’s around 130-140 bytes overhead per key in Redis which is significantly larger than the data we’re storing.

However, given you can scale RedisGreen to 30GB and we use a dedicated store for sessions, it seems we could support 100M sessions without any real problems so perhaps there’s no point in trying to optimise this. But let’s do it anyway, because it’s interesting, and it could save us some cash on hosting costs.

Iteration 1: Binary packing

The first change we can make is to turn the hex session ID back into binary, which almost halves the size of the key. Redis strings are binary-safe so we don’t need to worry about any encoding issues there, but we need to make sure we’re dealing with ASCII-8BIT strings in Ruby rather than the usual UTF-8.

def self.key(id)

"session:".force_encoding('ASCII-8BIT') + [id].pack('H*')

end

We can also make the data much smaller by switching to the MessagePack format and using single byte keys rather than the full attribute name:

def save!

ttl = expires_at - Time.current

data = { i: identity_id, x: expires_at.to_i }.to_msgpack

redis.setex(self.class.key(id), ttl.to_i, data)

end

This of course needs some corresponding changes to the find method:

def self.find(id)

data = redis.get(key(id)) or raise 'Not Found'

attributes = MessagePack.unpack(data).merge(id: id).with_indifferent_access

attributes[:identity_id] = attributes.delete(:i)

attributes[:expires_at] = Time.at(attributes.delete(:x)).utc

new(attributes)

end

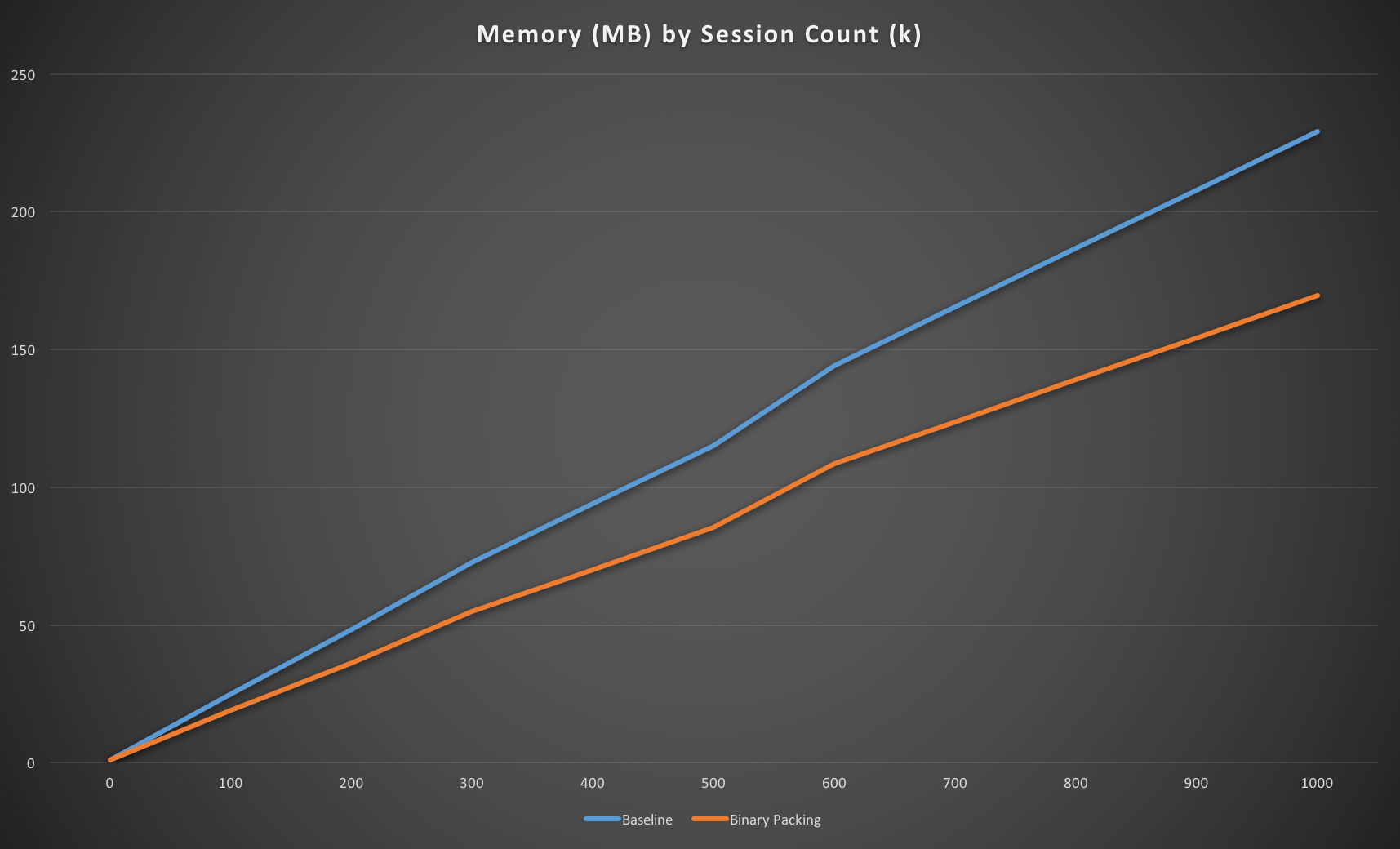

These changes give us a 25% reduction in memory usage, which isn’t as much as you might expect given we’ve dropped the key from 48 to 28 bytes, and reduced the data from an average of 45 bytes to around 15.

However, taking into account the previous observation that there’s a per-key overhead of 130-140 bytes in Redis things do match up. The old key/value was 93 bytes which with overhead is around 230, and the new one is 43 which with overhead is 178. As 178/230 = 0.77 it’s fairly good validation that the cost per key really is significant.

Iteration 2: HASH per session

We know that reducing our data size isn’t going to get us much further as we’re dealing mostly with overhead now. But just to exhaust the possibilities for a key per session, let’s measure using a native Redis HASH to store the session attributes using hmset and expire. These are wrapped in a transaction using multi to ensure that we don’t have any non-expiring sessions.

def save!

ttl = expires_at - Time.current

redis.multi do |r|

r.hmset(self.class.key(id), :i, identity_id, :x, expiry.to_i)

r.expire(self.class.key(id), ttl.to_i)

end

end

This needs a bit of a change to the find method to use hgetall.

def self.find(id)

data = redis.hgetall(key(id)).with_indifferent_access

raise 'Not Found' if data.empty?

attributes[:identity_id] = Integer(attributes.delete(:i))

attributes[:expires_at] = Time.at(Integer(attributes.delete(:x))).utc

new(attributes)

end

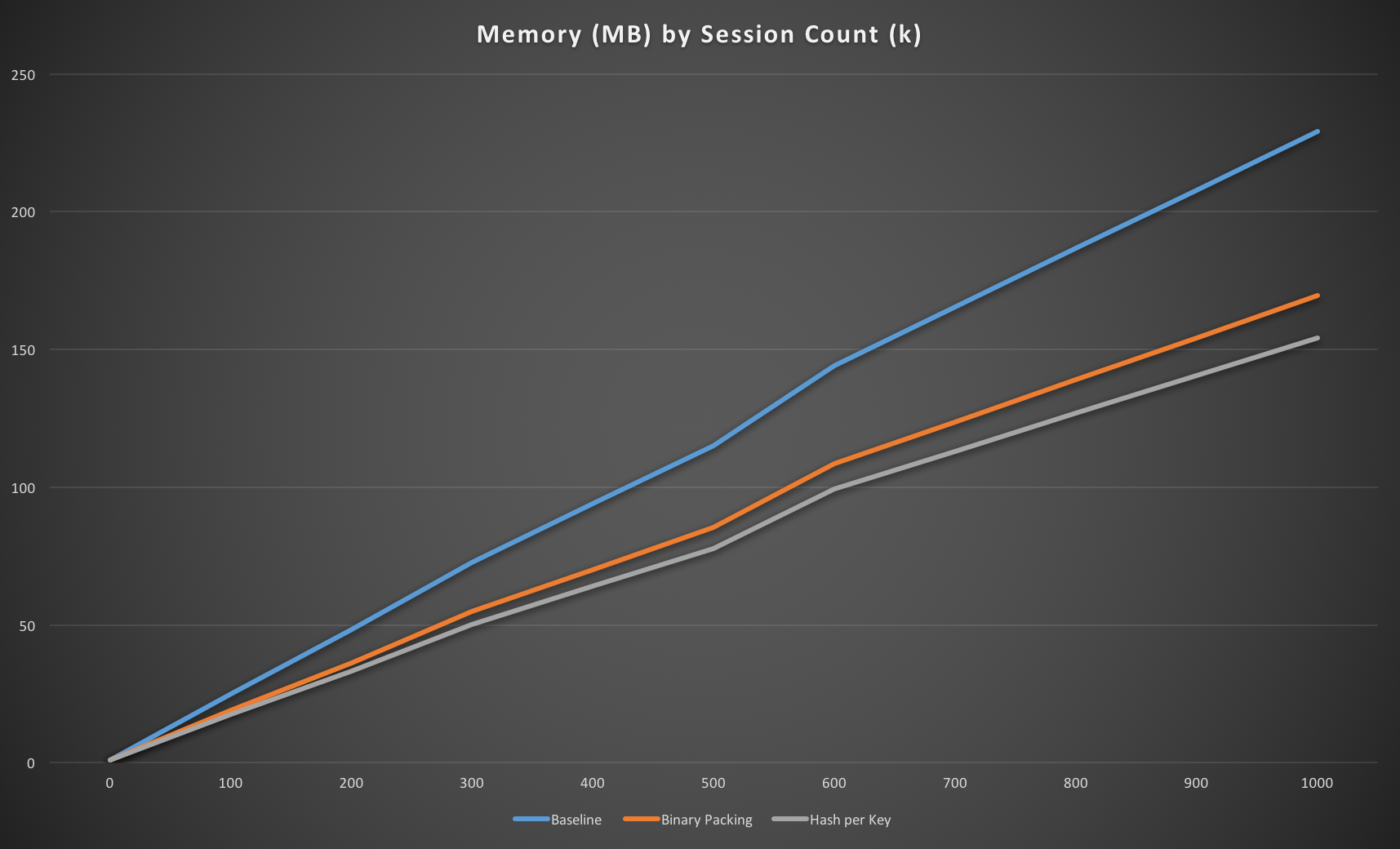

Making this change shows a small improvement over the msgpack serialised value so if you’re ever wondering whether to serialise attributes into a blob then, at least from a memory usage point of view, you shouldn’t as Redis can persist it more efficiently than you can.

With a couple of changes to convert the key to binary and use a Redis HASH to store the values rather than JSON we’ve improved the memory usage by almost 35% which is definitely worthwhile for a couple of changed lines of code. However, if we want to do better than that we’re going to have to change tactics and stop using a key for each session to avoid the overhead it incurs.

Iteration 3: Partitioned HASH + ZSET

The Redis memory optimisation page suggests that by storing multiple sessions in a partitioned HASH we can avoid the per-key memory overhead associated with each session. Unfortunately though, it’s not possible to set an expiry time on the keys within a HASH.

To allow us to expire they keys, we’ll store the session ID in a ZSET scored by expiry date, and then have a background job that can walk through those and remove expired sessions from the HASH before deleting the expired range from the ZSET. This is clearly more work than just setting the expiry in Redis.

We need a number of different keys, and using the first two characters of the session ID as the partition identifier will give us 16**2 = 256 partitions.

PREFIX_SIZE = 2

def self.data_key(id)

"session:data:#{id[0..(PREFIX_SIZE - 1)]}"

end

def self.expiry_key(id)

"session:expiry:#{id[0..(PREFIX_SIZE - 1)]}"

end

def self.sub_key(id)

[id[PREFIX_SIZE..-1]].pack('H*')

end

The save method needs to change to use hset and zadd to add to our HASH and ZSET structures respectively, again wrapped with multi.

As we can’t store a HASH within a HASH we’re going back to serialising the data in msgpack format. We could alternatively use two HASH structures per session, session:identity:* and session:expires:*, and store each attribute separately, effectively using Redis as a columnar store. However, the key is fairly large here (around the same size as the serialised session data) so duplicating it across hashes would use more memory, and would also mean the find method has to do two fetches instead of one.

def save!

data = { i: identity_id, x: expires_at.to_i }.to_msgpack

sub_key = self.class.sub_key(id)

redis.multi do |r|

r.hset(self.class.data_key(id), sub_key, data)

r.zadd(self.class.expiry_key(id), expires_at.to_i, sub_key)

end

end

Find now uses hget to get the serialised data from the appropriate HASH.

def self.find(id)

data = redis.hget(data_key(id), sub_key(id)) or raise 'Not Found'

attributes = MessagePack.unpack(data).merge(id: id).with_indifferent_access

attributes[:identity_id] = attributes.delete(:i)

attributes[:expires_at] = Time.at(attributes.delete(:x)).utc

new(attributes)

end

I’m not going to show the code for the job that has to clean up the sessions here because it’s not relevant to the memory usage.

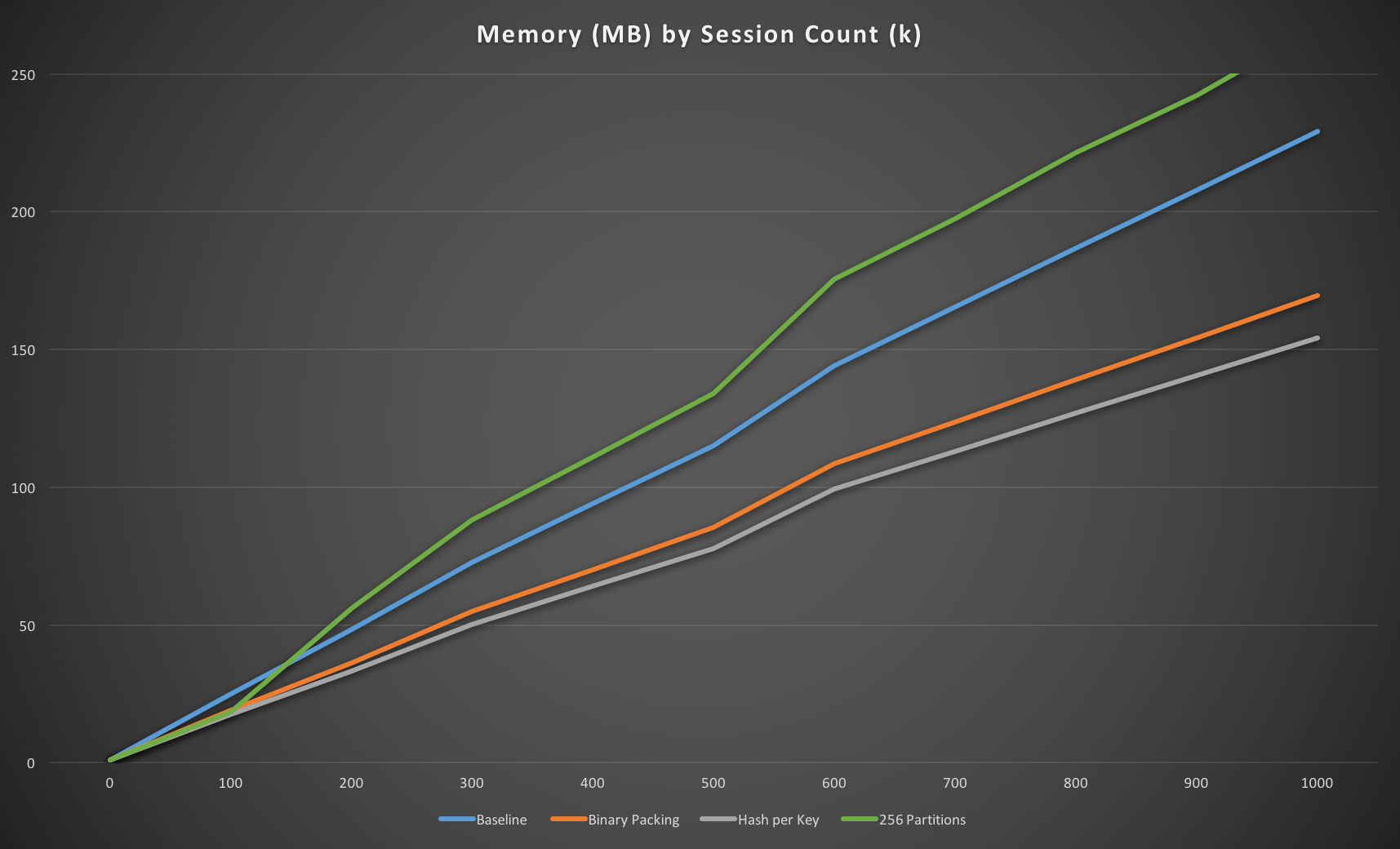

So, how does this fare compared to the key-per-session approaches? Perhaps surprisingly, fairly terribly! It’s around 15% less efficient than the baseline approach, and almost 60% less efficient than the optimised one.

How can that be the case?

We’d expect to see (15 + 135) * 256 = 38,400 bytes for the HASH keys and (17 + 135) * 256 = 38,912 for the ZSET keys, but that’s negligible here. The HASH should be storing a 19 byte key and 15 bytes of data, which is 34MB and the ZSET should be storing a 19 byte key and a 4 byte integer which is 23MB. So why is the overall usage nearly 270MB instead of ~60MB?

Well, given we’re storing 2M keys here (each key is stored twice) and we’re using an additional 200MB it looks rather like we’re still incurring fairly significant overhead from Redis, approximately 100 bytes per key, which is less than at the root but still very significant.

At this point we have to question whether this result seems plausible, or have we got a mistake in our testing methodology? Looking again at the Redis memory optimisation page it seems that in their optimisation they did see nearly an order of magnitude reduction so clearly there is a lot of overhead in a HASH, and this Redis memory usage page indicates that HASH and ZSET structures have have similar overhead to each other, and much more overhead than SET or LIST. Given that, the numbers do look plausible.

So why didn’t we achieve the same improvements as the Redis memory optimisation page?

Well, it turns out we didn’t do enough maths before choosing the partition size. The memory efficiency in the optimisation approach is gained by using the ziplist representation but these have to be fairly small. The default maximum number of entries is:

hash-max-ziplist-entries 512

zset-max-ziplist-entries 128

With 1M sessions across 256 partitions we’re attempting to put ~4k entries into each which easily blows through the limit so they’re just being stored in the normal representation. In fact, even by 100k entries we’ve already put ~400 entries into each so we’ve already blown the ZSET limit and nearly reached the HASH one.

We’ll need to try again with more partitions.

Iteration 4: Partitioned HASH + ZSET with ziplists

Given 1M entries, if we want both the HASH and ZSET to stay as ziplists then we need at least 1M/128 ≈ 8k partitions, assuming that keys are distributed evenly between them, which they should be using a good random generator. Sticking with powers of 16 as the partition keys are easy to create from a hex identifier, we’ll go for the smallest power that covers this which is 16**4 ≈ 65k.

PREFIX_SIZE = 4

That one character change takes memory usage from being 15% worse than our baseline to almost 70% better, so clearly ziplists are massively more memory efficient than the normal representation. We’d expect to have around 15 entries in each of the structures by the end so we’ve still got plenty of room to add more sessions before they exceed the ziplist limit.

Looks like we have a winner, at least in terms of memory usage! However, this isn’t the whole story. We’re only looking at a small number of sessions here and as we start to insert more of them things will change.

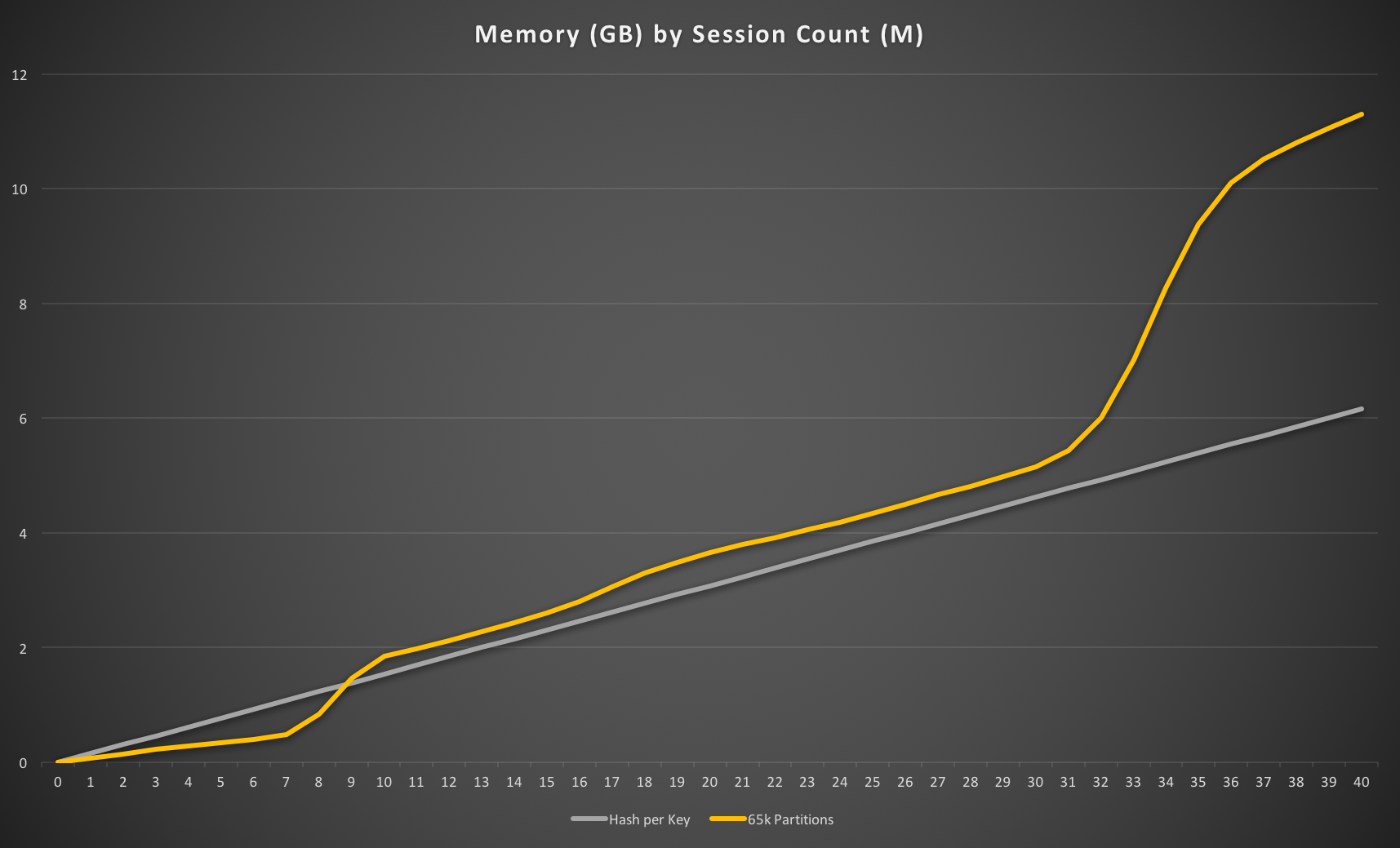

With 65k partitions and the standard settings of 128 entries in a ZSET and 512 in a HASH before the efficient ziplist format is converted to the normal representation we’d expect to see the ZSETs being converted once we have ~8.5M sessions and the HASHes being converted at around ~33M sessions.

Extending the lines to cover tens of millions of sessions we can see the trend, and the points where the ZSETs and then the HASHes are converted to their normal representation are evident on the 65k partitions line at around 7-10M sessions and 31-35M sessions respectively. The approach becomes less memory efficient than our optimised key-per-session approach at around 9M sessions, once most of the ZSETs are converted.

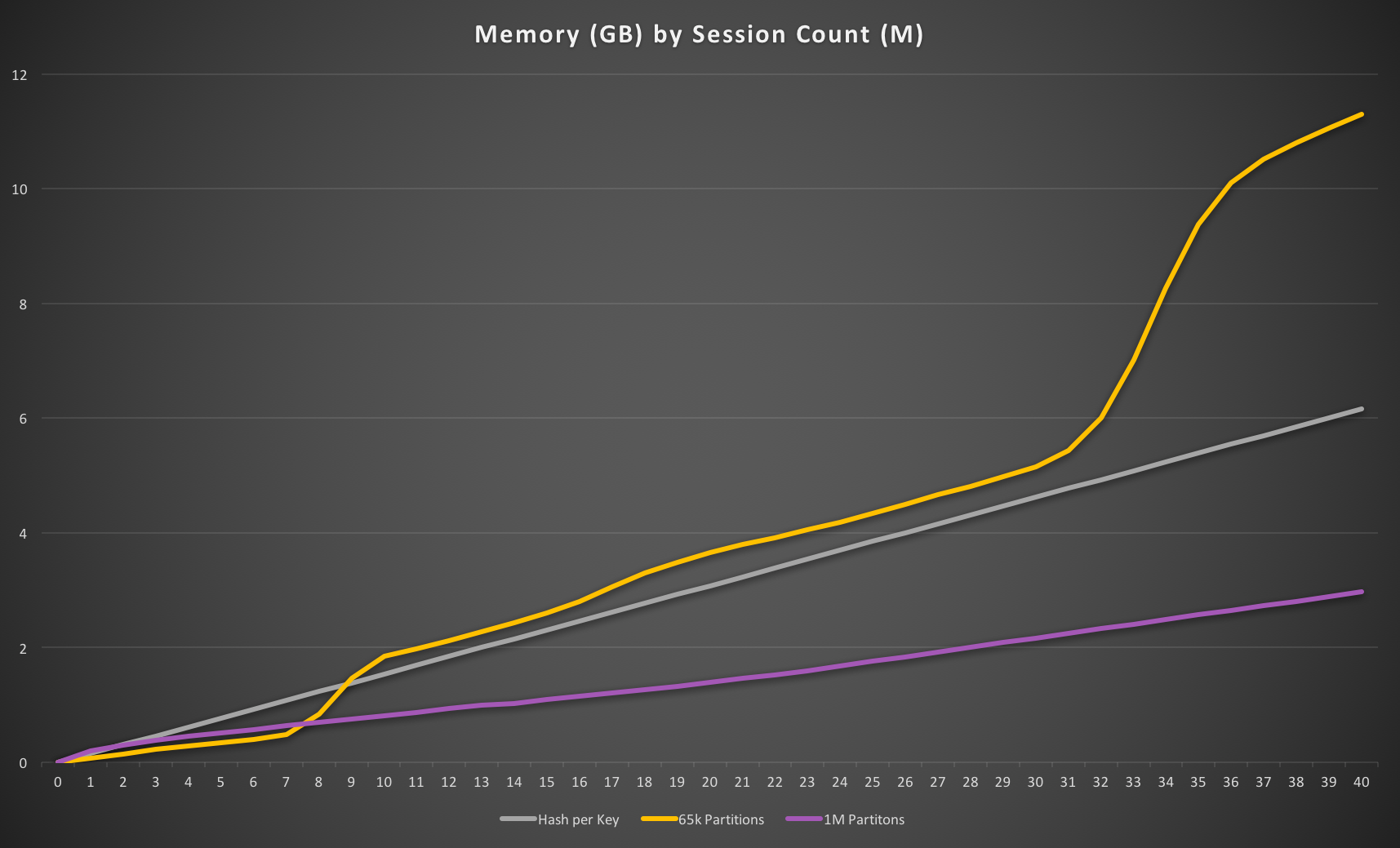

If we used a higher number of partitions, e.g. 16**5 ≈ 1M then we’d be wasting a lot of space with low numbers because it would effectively be two keys per session until we have over 1M sessions. However, as more sessions are added these ziplists will start to fill up more efficiently and we’d expect to see the memory usage be very efficient until around 100M sessions.

This is exactly what we do see, with 1M partitions becoming more efficient than key-per-session a little after 2M sessions, and more efficient than 65k partitions at around 8M sessions once the former’s ZSETs start to be converted to normal representation.

And now we really do have a winner for very large numbers of sessions. Managing 100M sessions using this approach would cost us about 6.5GB of memory as opposed to 23GB with our original approach or 16GB with the optimised key-per-session approach. Putting that into cold hard cash, it means we could run on a RedisGreen X-Large 7GB server at $779/month instance rather than a 30GB one at $2499 so hosting costs would be reduced by two thirds, over $1700/month. More than enough for a few team lunches.

Conclusions

The basic approach of serialising a JSON blob (or, better, a msgpack blob) into an expiring key is sufficient for managing sessions for all but the very largest of sites; you can handle over ten million sessions in less than 2GB of memory and Redis can handle at least 250 million root keys. Unless you’re dealing with a huge number of sessions there’s probably not much point in doing anything more complex because hosting is relatively cheap and dev time is relatively expensive.

If you do choose to partition then choosing too small a partition size is worse than not partitioning at all; you use significantly more memory than the basic key-per-session approach because you’re incurring significant overhead in two data structures, and it also increases the complexity of your code. However, getting the partition size right means you can make significant savings in memory usage – almost 70% reduction from the baseline approach and 55% over the hash-per-session option.

As a rough guideline the number of partitions you should choose is the number of items you expect to store (N) divided by the lowest *-max-ziplist-entries value for the type of data structures you’re using (Z) multiplied by 1.2 to give some leeway before the ziplists start being converted.

Of course, that’s just a guideline. You should measure to make sure you’ve got it right.