Every service is an island

We had an incident yesterday. It wasn’t that bad as incidents go, but it got me really worried — it’s something that has the potential to become much worse as we move towards a distributed, multi-service world.

Editor’s note: the issues described here have since been fixed.

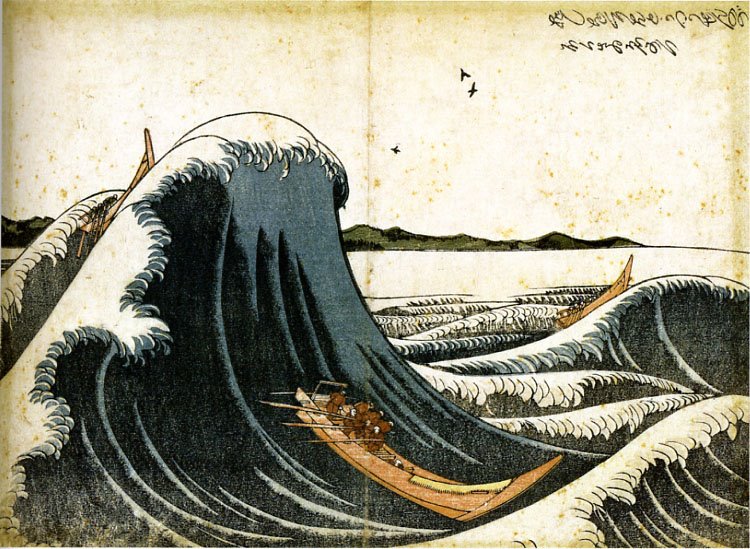

You do not want this to happen when you’re on call.

Source: Oshiokuri Hato Tsusen no Zu from Wikimedia commons, public domain.

What happened: hot path service chaining

Our APIs are calling services when responding to HTTP requests — synchronously.

It doesn’t really matter which, but a few concrete examples probably help: we

call into identity-service when checking sessions for rider app API calls, and

restaurant-targets when displaying restaurant listings to consumers (to

predict when we’ll be able to deliver delicious food).

Yesterday, those services became partly unreachable; their apparent response time increased and many requests to those services timed out. This cascaded into more and more of our web workers being blocked waiting on those; then unrelated requests timing out; and ultimately a degraded experience for all users.

We were lucky: the underlying issue resolved itself within a couple of minutes, so most people barely noticed anything.

The frustrating thing is that the services themselves worked perfectly fine during the outage. This was just a transient network issue.

Why this is bad: runtime service coupling

Because this is an architecture design problem.

The Internet is a harsh place, and services will fail. Where it gets worse is that things will fail unpredictably, and uncleanly — they’ll slow down instead of failing, for instance.

This is why if we want to make our user experience (for customers, riders, etc)

reliable, it doesn’t matter much how reliable we make identity-service,

restaurant-targets, or other services: if they’re called synchronously when

serving users, things will fail, and cascade into general failure.

In other words: when services are tightly coupled (by making synchronous calls to each other), every service is a single point of failure. Which is another way of saying things are still monolithic, from an operation perspective if not from a development perspective.

In the identity-service example, almost any call to the Rider API results in

a call to the identity service, to check whether a given session token is valid.

We informally call this a “hot path” because any service involved is “hot” —

they’re all required for things to work.

Fixing our architecture: bulkheading and event driven services

Circuit-breakers and bulkheads will likely be mentioned. They help somewhat, but they will not fix the main issue: we’re talking to other services on the “hot path” of serving users, and things will fail unpredictably.

Part of the reason is that tech operations rely on fairly consistent performance

and usage of resources: scaling up/down is not instant, for instance; amongst

other well-known

constraints.

If calls to identity-service instantly start taking 4x the time, its circuit

breaker will not blow its fuse, but the rider API will still go down before

autoscaling kicks in.

This applies whatever the bulkhead is: rate limiter, circuit-breaker, read-through cache. All three wil help reliability but not guarantee fault isolation, because they support only known failure modes.

The long-term solution is a design style I’ve been promoting for a while with

RESN and

routemaster. The general idea is

that every service can form its idea of the state of the world, by passively

listening for notifications from other services; act upon this representation

without assuming the state is fully up-to-date; and notify other

services/clients in turn as appropriate.

Here, the identity-service emits a bus event whenever a session is created.

The rider-api listens to those events to populate its local cache of valid

sessions. Whenever a request hits the API, only the local cache is checked.

With this approach, bulkheading becomes unnecessary for read operations

(although it still has its place for write operations). All reads are

essentially become service-local. This is visually obvious in the second half of

the diagram above: on the get orders path, no other service than the

rider-api is involved.

Going further

I’ve only touched the surface of the reliability benefits and design constraints of event-driven distributed systems here. The approach above can be generalized for write operations too, in some cases where reliability is paramount.

Yes, this is difficult. It means a very asynchronous design. It means procedural HTTP transactions often aren’t possible and you’ll need callbacks, web hooks, async notifications of some sort in some cases. It means you may need revisiting user interfaces. But it’s possible and avoids the kind of reliability issues we’re seeing at our scale.

If you want highly reliable distributed services, at the cost of some mild consistency headaches:

Make every service an island.