Data Sink

Our applications generate a lot of interesting data, but it’s not always simple to find the right way to collect it. We wanted to make it easier, so we went to the drawing board, and here’s what we’ve come up with.

The need for a sink

Our application services, naturally, generate a lot of data. Some of it belongs to the service’s domain, is persisted to the service’s database and circulated to other applications through Routemaster events. Then we have application logs, which we rely on for debugging and to quickly check that things are running as they should. We also have metrics, which enable us to track the behaviour of our systems over time, and alert us if things get out of bounds.

We quickly realised, however, that there is a lot of data we’d like to capture but doesn’t fit neatly in any of the above categories. For example, we’d like to keep detailed logs of the inner working of our dispatcher algorithm: these definitely don’t fit into the database (they will never be read by the app), but sending them out as logs would make it tricky to analyze them later (and increase our log volume considerably, creating noise and raising costs). Or, we want to track user behaviour events: these are generated in large volumes and need to be available for easy later processing, but again don’t belong to the application’s domain model, and would put needless strain onto the database if we were to persist them there. Also, for some models, we want to keep track of all data changes. For some time, we have been versioning records to a separate database, but that soon became impractical.

One way to handle these use cases would be to have a separate storage dedicated to write-heavy, ephemeral data; but apart from introducing new complexity both to the overall architecture and to each application’s codebase, it would still leave us with different silos, and wouldn’t solve the problem of processing the resulting data at scale.

Here comes the handyman

So we determined we needed a solution that allowed us:

- To easily send data out of an application, without requiring the app to worry about the details of the archival

- To store the raw data as received from the app in a format that’s durable and easily queryable

- To be able to treat the data events as a stream, in order to post-process it or to build real-time tools around it

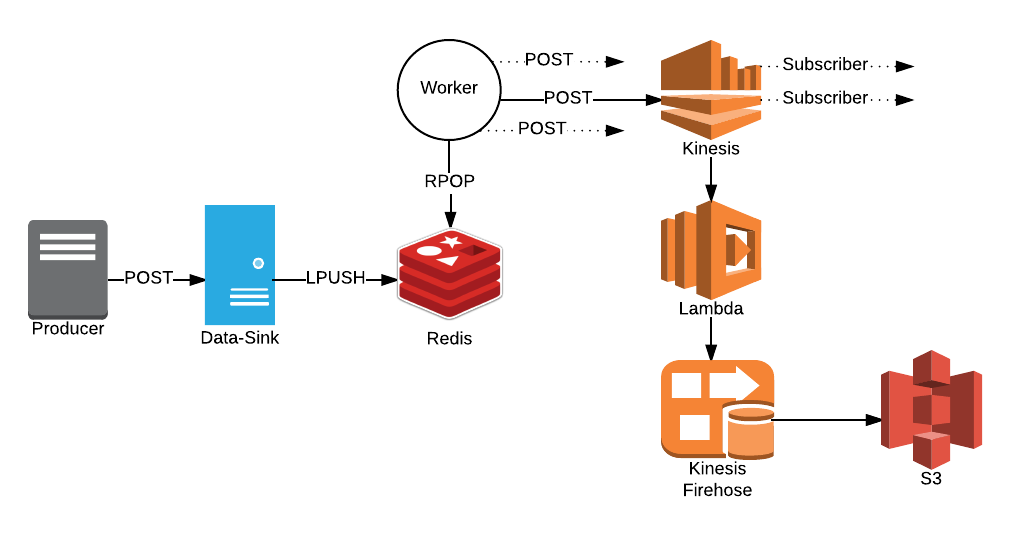

In order to make it as easy as possible for the producer application to send data, we decided to expose the simplest possible service: an endpoint that would accept data via POST, and take care of persisting it. Truly fire-and-forget.

For the destination format, we settled on archiving the application data as-is into Amazon S3. Having data in S3 has many benefits: it’s relatively cheap, reliable, and works well with our Data Warehousing tools. With Snowflake - our Data Warehousing platform - we can store raw JSON data into S3, and then query it via SQL just like regular structured data. Magic!

So the question became: how do we write a stream of data to S3, all without preventing the possibility to tap into the data stream in real-time? S3 doesn’t provide an “append” operation, so our data-sink app would have needed to take care of the buffering; and if we wanted to accept subscribers for the data streams, things would have become rather more complicated.

Luckily, AWS already provides the perfect tools for what we need. The first, Kinesis Firehose, is a stream that forwards everything it receives to S3 (it can also be configured to push data to Redshift or Elasticsearch). The second, Kinesis Streams, is a streaming engine that forwards a data feed to any subscribers. Together, these ensure that our data is archived, but can also be processed on-the fly if needed. The last piece of the puzzle was how to connect the two: that is easy to do with an AWS Lambda function which, when connected to the Kinesis Stream, will pass each message to the Kinesis Firehose. There we have it, the best of both words!

Turning the faucet on

Having identified the needs, we just needed to put everything together. We wanted something that

- would be as easy as possible to set up and to use for the producer apps

- would be reasonably fast, enabling us to send large amounts of data without slowing down the producer process too much

- would be as reliable as possible (although we don’t want to offer delivery guarantees: our use case can afford occasional missed messages, if that doesn’t happen too frequently).

Therefore, we tried to keep things as simple as possible. Our service exposes a POST endpoint for each “stream”, which does only one thing (after having authenticated the caller via Basic Auth): push the POSTed body onto a Redis list. The body is written as-is, but wrapped in a MessagePack tuple which contains the name of the stream and a timestamp (for housekeeping).

In the background, a worker process polls the Redis list, POPping messages and sending them to the right Kinesis Stream via a thread pool.

That’s it! Messages are ingested, and after a while, they appear in S3, under a path corresponding to the stream name: data finally lives where it belongs, and we can post-process it and analyze it as much as needed.

To make it straightforward to create all the resources needed for a “stream”, we also added a migration functionality: once a stream is defined, a rake task will take care of setting up the Kinesis Stream, the Firehose, and the Lambda connecting the two. In essence, this hides all the complexity of the underlying data flow from developers, who just need to add one line of code to have all the infrastructure needed to push data to S3.

Make it rain

The simplicity of this service allows it to be very responsive, and easy to scale. The endpoint responds in less than 5ms, plus the time to transfer the payload. Our worker task currently processes 2K requests/min; if the load increases, the application can be auto-scaled when the number of messages in the queue go over a certain threshold.

We are hopeful that having this tool available will enable our engineers to feel more confident in storing what goes through their applications for later analysis; at Deliveroo we are a data-driven company at heart, and we believe that there are often valuable insights that can be obtained when data is available. By making it simple to archive data and analyse it later, we hope we’ll see new and creative uses for the information our systems produce!