Tired of waiting for pull request reviews? Play Pull Request Roulette

You work in a medium or a large team and you find yourself tapping your fingers waiting for someone to review your PR. Days pass and nobody volunteers. Your code gets stale, version control conflicts emerge. What to do? Convince your team to start playing Pull Request Roulette. It’s fun and it works!

The PR problem

As our Consumer mobile teams began to grow, we started experiencing delays getting our pull requests reviewed.

We’d code our task then open a PR in GitHub and find someone to review it.

We use the +2 rule, which means every PR needs 2 +1s from the team before being merged.

So far so good…but people seemed less eager to “volunteer” to review PRs. So PRs would stale, the code would become old, conflicts with other PRs would start to appear and soon we were pretty much in “Rebase-Or-Merge-Hell”. Sounds familiar? Read on.

Bobby to the rescue

One of our awesome colleagues in the iOS team, Robert Saunders (aka Bobby), took the initiative to start a series of PR & QA Kata meetings with the team (totally optional) to get to the bottom of the problem, the scientific way:

- identify the bottlenecks

- choose actions to improve it

- measure effectiveness

This was a great way to kickstart a conversation and encourage everyone to share both problems and solutions. By measuring the amount of time each PR would remain open, we’ve started getting a clearer picture of the problem: from looking at the data, 15% of iOS PRs and 20% of Android PRs took more than 2 days to merge (not including weekends). Some were acceptable reasons, like dependency to backend being ready for testing or finalizing design & content. But in most cases, it was just the lack of reviews that was causing the bottleneck early on.

Ideas to make your PRs more review-friendly

I am in awe at my team’s desire to self-improve. Over the time I spent working in the Consumer Android team, a lot of great feedback and ideas have emerged from self-organised meetings like the one mentioned. And it’s not just the Android team.

I’ll list some of our DOs and DON'Ts that might benefit others too.

1. DON’T open huge PRs

You are definitely going to scare people if you open a PR that has 50+ files changes (excluding trivial things like renames). Being 100% guilty of this myself, I can say it’s very hard to find a good solution. Nobody likes abandoning their work for an entire morning to check someone else’s PR. Not to mention that even the most disciplined developer will most likely lose focus after 20 minutes of looking at somebody else’s code.

Instead, DO split the PR in multiple parts

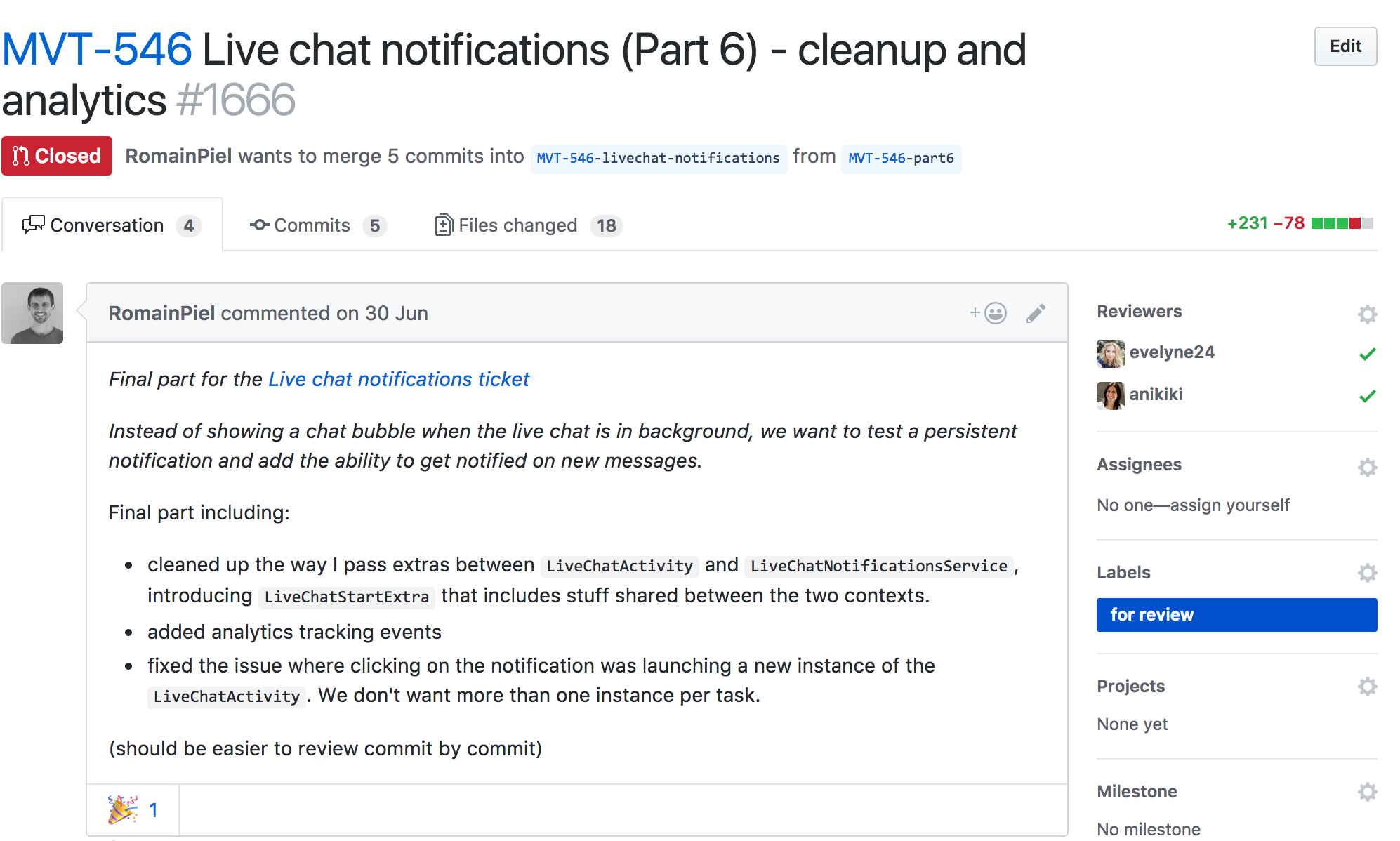

This can be done by branching off your parent branch into smaller parts, each with a separate PR, Part 1 to 4, for example. This forces you to think about splitting your work into chunks that can be reviewed and tested individually. Because the PR is now smaller, people will more likely look at it and not forget half of the changes by the time they’re finished reviewing it. The hard bit with this approach is that you won’t have a clear picture of what goes where in the beginning. It takes effort and discipline (and a lot of Git wizardry) to end up with clean cuts between branches and testable code in each. Some colleagues have become very good with this technique and I’d say that it has helped us move faster.

Another similar technique, for those who prefer a single branch, is to have clean cut commits, so that you read the PR “commit by commit”, rather than all at once.

DO keep your renames / moving files in a separate PR

It’s easier for everyone if you make a PR that only contains trivial changes like renaming or moving files. These are trivial but if not done properly, they ripple through the whole project and you suddenly realise renaming one class caused 30+ other files to change. Keep them separate, in a PR before or after you have done your actual code changes. Same goes for Java-to-Kotlin conversions. Because the file type changes, it’s nearly impossible to review them. So first, make a PR with just the conversion, and then one with the changes applied to the new file type.

2. DON’T just use the ticket number in the PR description

Having a tiny or non-existent description of what you’re doing in your PR doesn’t help anybody. Yes, we link the PR with the Jira ticket, so anyone can click through and read a summary, but that’s not the purpose of a PR description. The ticket alone doesn’t provide enough context about what you’re trying to achieve and your reviewers might have a different understanding, if left alone to decipher your task.

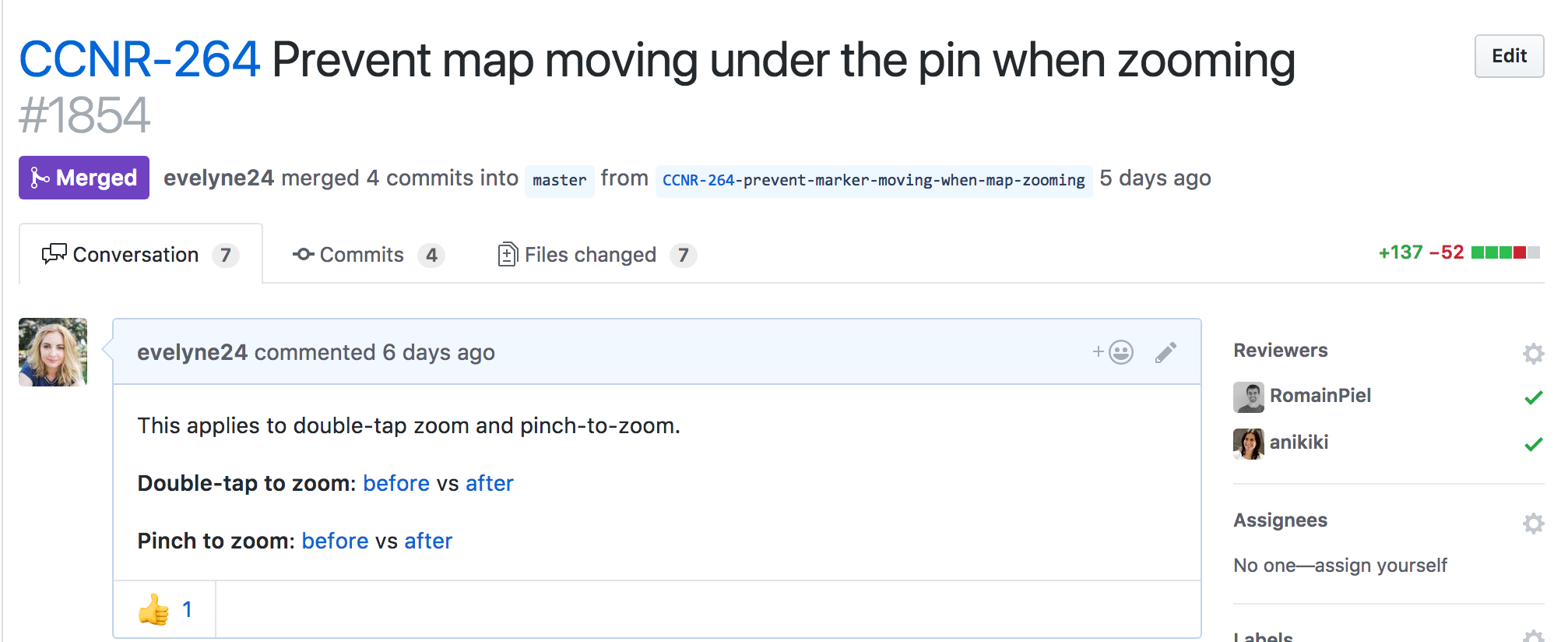

Instead, DO provide a reasonable description, some screenshots or a video of how things work

For non-UI code, a good description highlighting what you’re trying to do, will work wonders for your reviewers. People reviewing it will find it easier to spot inconsistencies and avoid misunderstandings if you provide an upfront understanding of the task at hand and break it down in a few bullet-points.

For code involving UI changes, having a before-and-after screenshot or a link to a video will help people visualize the change better and will show that you made an effort to test your own code before submitting it for review. Depending on your platform, you could even provide an executable binary that can be immediately downloaded, installed and tested by your reviewers.

3. DON’T wait until the last minute to open your PR

This works well in at least two situations. First, when you’re not sure if the solution you’re coding is the simplest or best way. Maybe you’re in an unfamiliar territory. That’s fine! Opening a PR and asking for feedback ASAP will stop you from spending days working alone on something you might need to refactor after review. Second, when we prototype things fast (for example improving the architecture or trying out a new language) and want to check if the team is on-board with the proposal. We label these prototype PRs “spikes”.

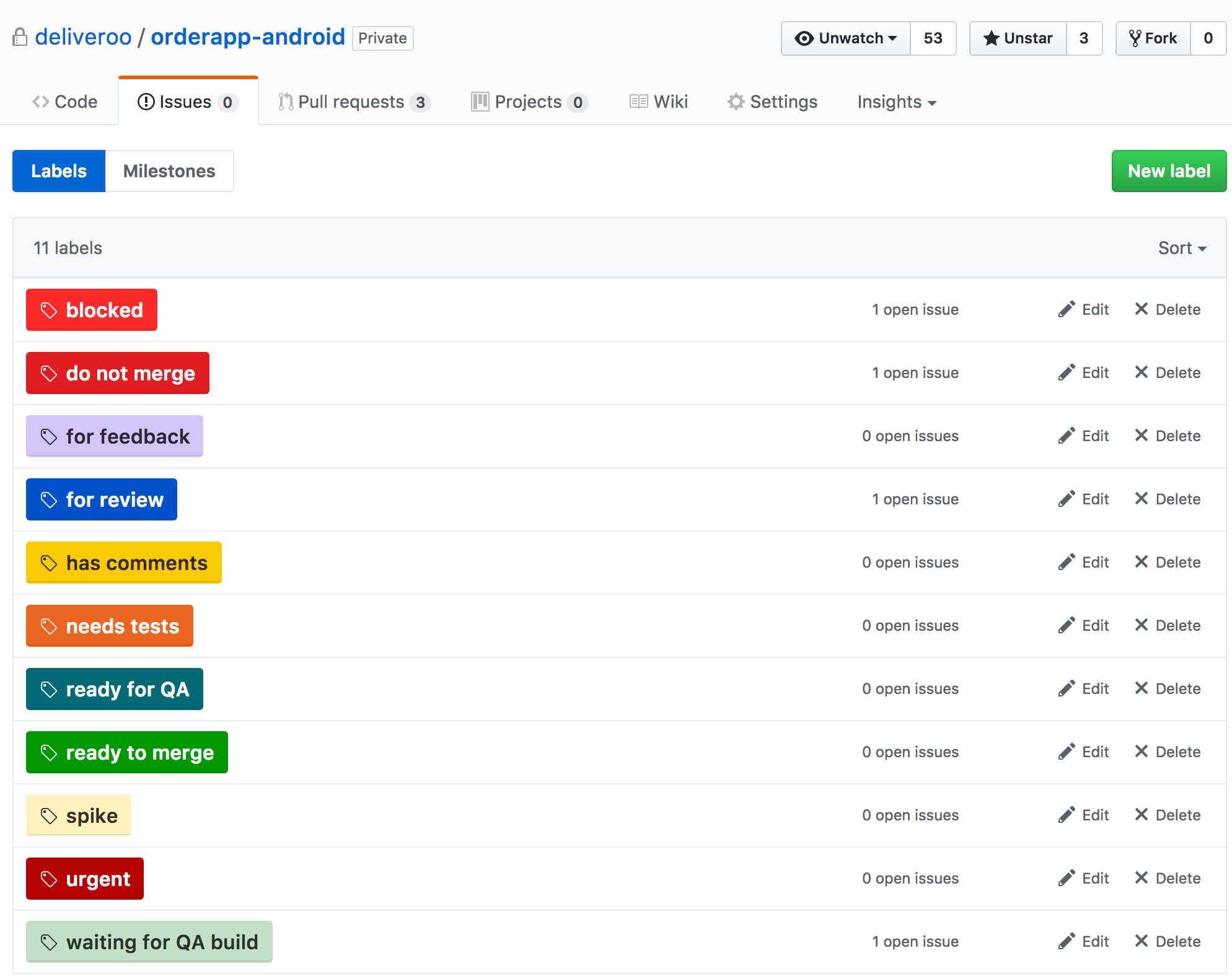

DO label your PRs accordingly

GitHub provides a nice and simple way of labeling things. Different teams have different labels, but in general, we use them to indicate the progress

of a PR, for example for-feedback, to-review, ready-for-qa, staged, blocked, spike etc.

4. DON’T just wait for people to volunteer to review your PR

As a last resort, when you’ve done all the improvements you can to make sure your PRs are review-friendly, and still can’t get people to look at them, take the reins and be proactive. In our team, we’re practicing something we called ‘PR Roulette’. In a nutshell, it’s about randomly assigning reviewers. If you practice +2s, then assign two random people in your team to check your PR.

Nowadays GitHub offers this feature by default when you open a PR. It even suggests which reviewers you should pick, based on people who have recently interacted with the files you’ve changed. It’s more likely they will have a better understanding of the changes while it’s still fresh in their minds. There are cases when those two individuals might be in meetings or on short deadlines with their own work. If someone has been assigned that doesn’t have the time, it’s OK to discuss with the team about a replacement.

If you’re not using GitHub or you want to spice it up, you can use a Roulette Name Generator to pick your reviewers. There are no written rules about how to play. Start by adding all the names and spin the wheel. It’s fun and you can improve your PR Roulette technique as you go.

By randomly assigning people from your team (or cross-team) your developers will feel more responsible for reviewing code on time, and in the long-term it will increase everyone’s knowledge of the whole project by exposing them to code they’re not as familiar with (important if you want to have bus-proof projects! 😄). We initially set out just to solve the problem of getting our code reviewed, but it turns out there are lots of other benefits to PR Roulette!