Shipping Quickly with a Large Team

We will walk through some proven techniques that we used to ship greenfield software quickly with a large team.

On the Payments team, we recently came up against a situation where we need to build a greenfield app, had tight deadlines, and had 7 engineers available. Amazing! there are 7 engineers available!… now how can we work effectively?

Should we adhere to the two pizza rule, where a team should not be larger than what two pizzas can feed? This is backed by science and is a great rule to follow. However, if we followed it, our team size would be 2-3, maybe 4 if we’re not very hungry that day. So we stepped back and thought about how we can meet the requirements and deliver this quickly, effectively, and have all 7 engineers contributing.

We shipped the product on time with all 7 engineers contributing. These were some techniques we used.

Design an Architecture

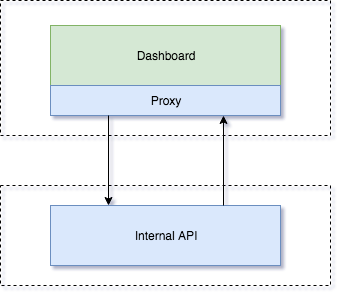

We needed a dashboard where users could login and perform specific money movement operations. The architecture should allow for future internal systems to interact with it. It needs to scale.

To minimize merge conflicts, allow for reuse, and build for scale, we elected to create two apps that both deployed independently and lived in separate git repositories.

Dashboard

We built a React front end which sat on top of a thin NodeJS proxy which routed requests to our internal API and provided a layer of security. It would validate the JWT’s against our identity server, as well as pass whitelisted authenticated requests to the API.

For context, the Deliveroo Identity server is an independently deployable service that authenticates users, in the case of this project, via Google Social Login. It then establishes whether to grant or deny the access request. If the grant is successful, then a JSON Web Token (JWT) is issued. This JWT is encoded and stored as a cookie in the users browser. It contains a mechanism to identify the user as well as additional attributes such as the time that it expires.

By using a thin middleware proxy layer, we didn’t need to write object mapping code to convert objects from the Go API into the Node App. This helped us get the product to market faster with a nice side effect of having less code to maintain in the future.

Internal API

We built an internal API in Go. This served as both the home for the domain logic, kafka consumers, kafka producers, and allowed other internal systems to be able to connect to this API in the future.

Establish Patterns

Now, we have a high level architecture in place, but before having the whole team start delivering features, it’s important to carve out some patterns.

With the react/node front end, we decided to use redux, axios, http-proxy-middleware, and jest. We carved out some patterns for making an API call, redux actions, reducers, and selectors.

On the Go API, we also set up some patterns including how we structure the API, http handlers, authentication, database access, api clients, and kafka consumers.

Once we had these patterns in place, more engineers were able to dive in and start building vertically sliced features.

Pair Program

Pairing can be highly effective. When a developer pairs, they get a built in design review, code review, and shared context. When one member is on holiday or ill, the task can still be worked on. Our team also determines when certain tasks can be split up and worked on in parrallel without paring: a divide and conquer approach.

Avoid Merge Conflicts

We had a situation where we need to build three aggregators that consumed information from another API, aggregate it, and surface it in a specific way. The output of these aggregators fed into the business logic of the app. Each one of these aggregators allowed a vertically sliced feature to function. It was paramount that these were delivered quickly so that our users could start trialing the product and providing feedback.

We struggled with 2 things:

- How do we name these “aggregators”?

- How can we get 6 devs working effectively on building these?

We weren’t sure what exactly to name them. We had good ideas, but they didn’t seem quite right. So we deferred the decision. We deferred it by creating 3 jira tickets, JIRA-111, JIRA-222, JIRA-333 with all of the details required to implement them. We established a pattern and an interface in go. We created individual interfaces in individual files. We named each file after the ticket number. All of the aggregators relied on a specific API client to consume the data, so we built that client ahead of time and used dependency injection to pass it into the aggregators. Once this was in place, we had 1 pair of developers working on each ticket.

aggregator.go

type Aggregator interface {

PAY111

PAY222

PAY333

}

pay111.go

type PAY111 interface {

GetPAY111Summary(name string, start time.Time, end time.Time) (ConcreteView, error)

}

pay222.go

type PAY222 interface {

GetPAY222Summary(name string, start time.Time, end time.Time) (ConcreteView, error)

}

pay333.go

type PAY333 interface {

GetPAY333Summary(name string, start time.Time, end time.Time) (ConcreteView, error)

}

By carving out a common interface, establishing a common patterns, splitting each interface into its own file, we had zero merge conflicts, and were able to build these all concurrently. Once we had these built, we really understood the domain much better and how they should be named. So we simply renamed the interfaces, renamed the structs, renamed the files, and done.

Summary

I’ve covered some techniques we used to build a scalable application rapidly and effectively make use of all of the engineers on our team. Using these approaches allowed all 7 engineers to build vertically sliced features with minimal merge conflicts, iterate, and ship quickly. A few other techniques we used which were not mentioned in this post were:

- Defining API contracts with protobufs.

- Building stubbed APIs. This is a pretty classic approach enabling a front end and backend to be developed in parallel.

- Having stories written for 1 to 2 sprints ahead.

- Descoping. We constantly asked ourselves what are the minimum things that need to be done to build this feature, and do we really need it.

If building scalable applications using react, go, kafka, and protobufs interest you, join us on the Deliveroo Engineering Team. We’re hiring!